The silent crisis of India’s healthcare sector

- By Prateek Raj --

- May 19, 2020

Healthcare, doctors, GDP, healthspending

Resident doctors are fighting the war against the COVID-19 crisis from the front lines. There is no dearth of showering of wordy and flowery gratitude for all their hard work and efforts.

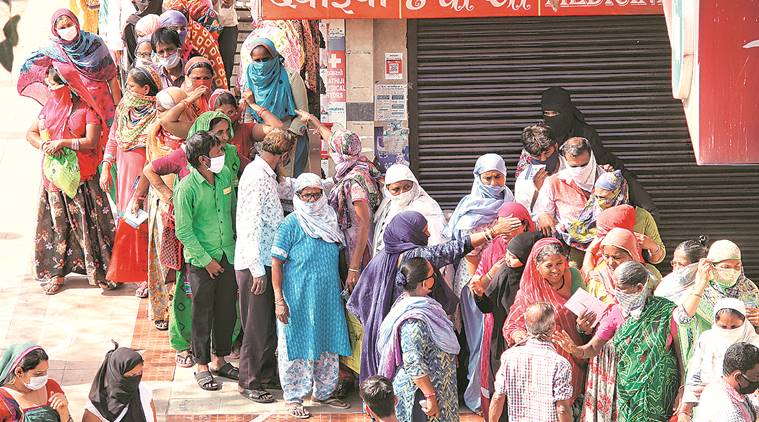

Young doctors in their early 30s, who chose the path of being a doctor over other lucrative careers, are earning between Rs 40000 to 50000 a month as residents, while doing frontline COVID-19 duty, exposing themselves to all the risks, with no hazard pay. If they wanted to leave after the crisis, to pursue a better career, they would be asked to pay a hefty bond in some states, such as West Bengal. On top of all this, there are reports from around India that resident doctors are being treated poorly (without basic equipment) with reports of their pay being cut or docked in some instances.

If such is the working conditions and pay incentives of top of the line resident doctors in their early 30s, what is the incentive left in this country for people to become a doctor? For a country that has abysmally low doctors per capita, such a poor incentive structure does not make the medical career any more lucrative, and the future of healthcare in India any more assuring.

Today if you want to pursue a well-paid career, a generic MBA seems to be a must. Opportunities for those who pursue expertise, in science and especially in medicine are meager. For someone in their 20s and 30s, being a YouTube “influencer” offers a more attractive career path than being a doctor. There is something broken about our economic system when being a highly educated scientist or a doctor is not a lucrative early career option, of the same kind as a bureaucrat, a consultant, or a Twitter troll!

Why are doctors, even those with decent medical experience in their 30s, treated as low paid “residents” when clearly they are qualified experts. Are they less capable, less intelligent, less hard-working, less rare, less essential professionals than the bureaucrats? The skills of Indian doctors are highly valued across the world. Then why can’t India value its own? Its true that bureaucrats in India are also paid only modest salaries, but they are afforded certain benefits which make their jobs lucrative to many including from the private sector. They are treated as babus, when resident doctors of their age are given little voice, neither within the profession nor outside. Why do young doctors not get comparable benefits?

Why can’t all the Indian doctors above a certain qualification, serving public healthcare, be enlisted in a national medical service (similar to the UPSC) and be afforded a decent seventh pay commission package that matches the depth of their expertise? This is also a recent request that the Federation of Resident Doctors' Association India (FORDA) has made to the Prime minister. Being a doctor is a social service, and they understand that such a service does come with some sacrifices. They are doing their job out of a sense of duty, not for the greed of money. Hence, doctors do not expect hedge fund manager salaries. But a good salary, a good package with a decent quality of life - what stops the government from offering them so?

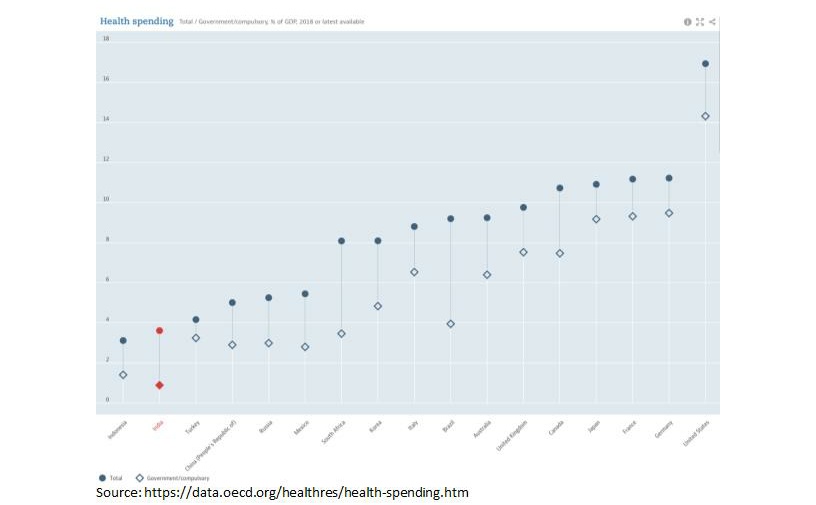

A major reason why paying generous salaries to the doctors, especially those who are young, doesn't cross the mind of Indian policymakers is because human capital - health and education - seems to have been a historical low priority of the nation. India’s government spends around 1% of the GDP on health (lowest among G20 countries), when China spends around 3%, the USA over 14%, the UK around 7.5%, and Brazil around 4%.

When there exists such a small kitty for health, is it a wonder that a pay raise for doctors never reaches the decision desk? At the same time, lack of private competition in the health industry further worsens the situation because doctors have no labor mobility. They work effectively within a government monopoly. While we can debate how much privatization should there be in Indian healthcare; yet the fact that competitive salaries must be paid to the doctors is a no brainer.

The condition of Indian resident doctors is also a reflection on the state of human development in India. Human capital in India has been ignored, first in favor of top-down industrialization during the pre liberalization era, and then of pro-business privatization in the liberalization era. Where are the much-needed investments in public goods? Even the much-anticipated stimulus package speaks the language of supply-side economics, ignoring the obvious fact that the coronavirus pandemic is primarily a health crisis, and a priority for the government must be to invest more in public goods such as healthcare. The machines, the factories, the bridges, and other “temples” have been given a priority in the country for far too long over the doctors, the teachers, the nurses, and the scientists, i.e. the actual skilled class of the country that holds it together. As human capital has been ignored, no wonder India has uncharacteristically low levels of human development: infant mortality is high, literacy rates are low, drop out rates continue to be up, and life expectancy still remains 10 years behind China.

We should hope that at least after the pandemic, our investment in public health will go up. For sustainable growth, a simple one-dimensional focus on businesses and capital won't be fruitful, and it will require a holistic approach. The pandemic is an opportunity for this understanding - of the importance of public health - to dawn. In the latest stimulus package the government has given an indication of increasing health expenditure, but the amount or percentage GDP terms were not specified. A significantly greater fraction of India’s GDP must go into healthcare. And with such an increase, the health workers, including doctors should get the respect, recognition, privileges, and the pay that they deserve.

Prateek Raj