Source for the Tea Garden picture- Photo clicked by Riya Kashyap Ghatowar at Hakomata Tea Estate, Biswanath Chariali, Assam

Reverse migration: An opportunity for the Tea Estates in Assam and West Bengal?

- By Habib Raihan and Anamika Deb--

- August 17, 2020

Share This Story

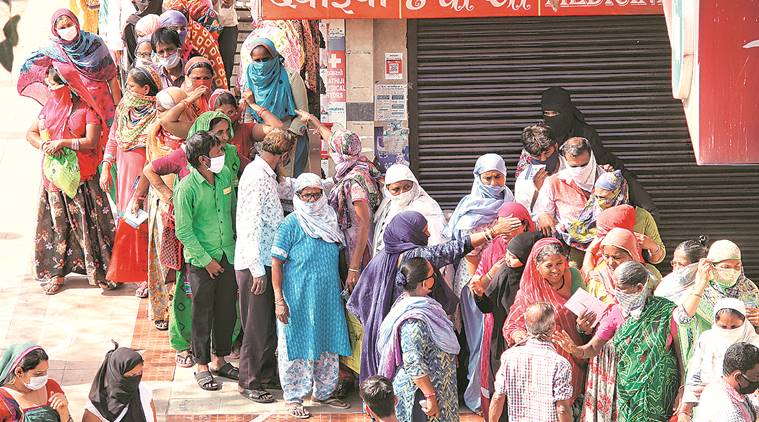

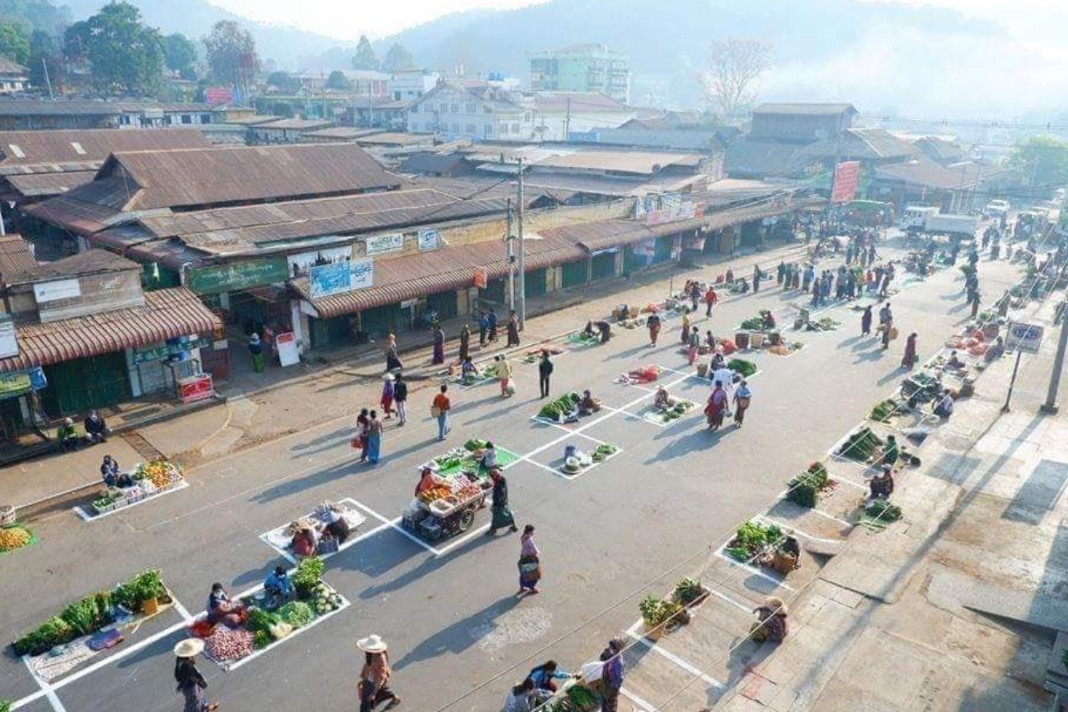

As the nationwide COVID-19 related lockdown eased, migrant workers began returning home. Several tea garden labourers who had left West Bengal and Assam in search of better opportunities have also returned. In the past, out-migration from tea estates had been a serious concern with several studies document difficulties with labour workers even as tea production rose. Thus, the return migration has the potential to re-invigorate the tea industry in a way that had not been possible even at the start of the calendar year.

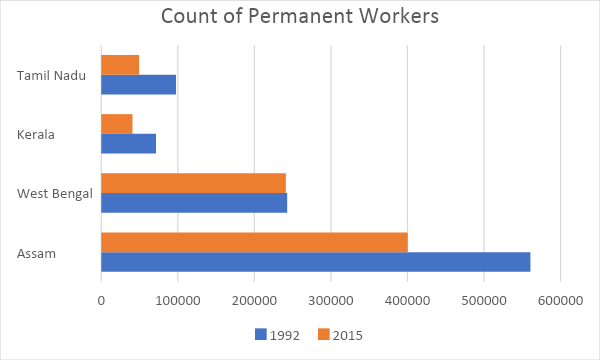

Figure 1 Workers and Tea Leaf Production, by States

Source: Bhowmik(1996) and Tea Board of India (2017)

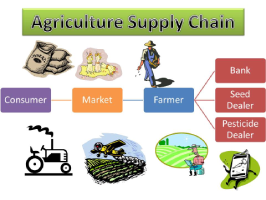

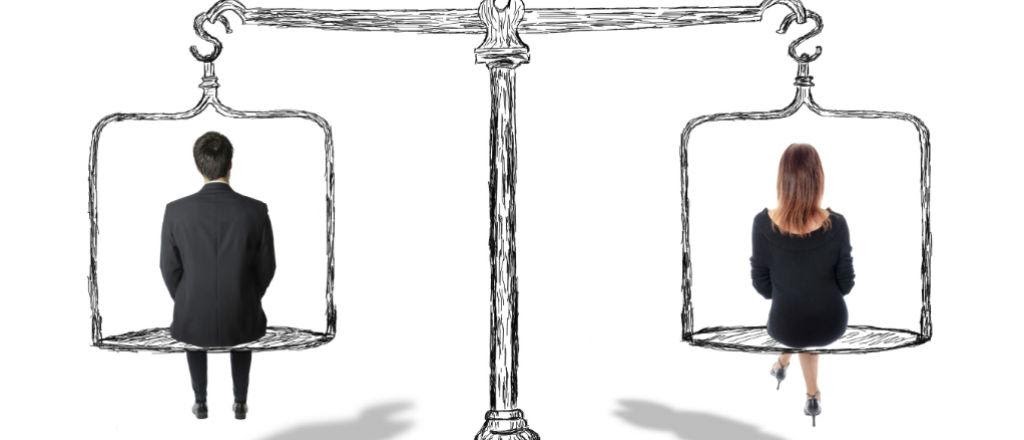

Workers in tea estates are of two types - permanent or temporary. The Plantation Labour Act of 1951 (PLA51) requires tea companies to provide housing, drinking water, and health facilities for permanent workers. Figure 1 records a decline in permanent employment in between 1992 to 2015 in all states, even as tea production has increased in Assam (51%), Tamil Nadu (61%), and West Bengal (93%). A decline in permanent workers can be explained either by a greater reliance on temporary workers or increasing mechanization in tea production. The increase in production is consistent with the rise in tea plucking targets set for workers. In north Bengal, the target had been 14 kg/day that has now increased to 20kg/day. Similarly, in Assam, the current target is 24 kg/day. With rising targets out-migration is a reasonably likely scenario, however, this is accentuated by the disparity in wages that labour receives across states captured in Figure 2.

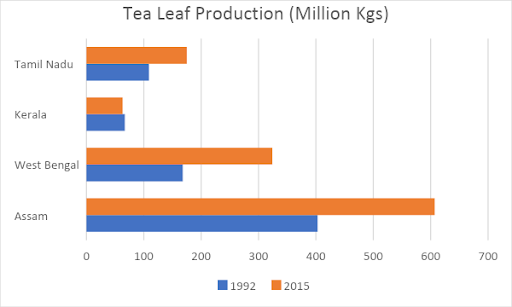

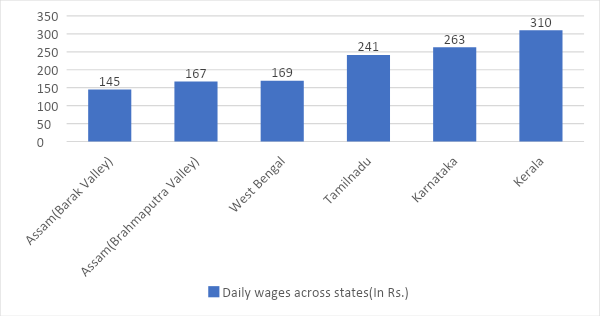

Figure 2 Tea Garden wages, by location

Source: Tea Board of India (2017)

Figure 1 shows tea worker wages in the south are much higher than in West Bengal and Assam. More than 7-8 lakhs workers have migrated to the other parts of the country. While some have moved within the tea and coffee sector to states like Karnataka and Kerala, others have found jobs in the construction and service sectors across the country. It is estimated that more than 2.5 lakh workers have migrated out of Assam and West Bengal to other tea estates with better wages and more favorable working conditions.

Out-migration has led to poor workforce practices and performance with absenteeism becoming common and lack of experience being the norm. While production has risen, the pre-COVID 19 decline in permanent workers indicates rising labour market shortages. Reverse migration allows for the possibility of re-invigorating the workforce both in volumes and in terms of skill and experience levels of the current workforce. A few tea gardens from North Bengal have already started hiring these returning migrants. R P Thapliyal, Chairman, Tea Association of India, north Bengal, said the daily manpower shortage is near 30 percent; most planters are managing with a 50% smaller workforce; employing the returning migrant may be a win-win situation!

The tea industry collectively has an opportunity to reverse conditions that had led to out-migration. Implementing benefits for permanent workers under the PLA51 would be welcome. The West Bengal government has been launching schemes relevant for tea workers (e.g. 5000 crores has been allocated for housing development project (Chaii Sundari)); using Financial Assistance to the Workers of Locked out Industries supporting benefits for returning migrants. The Alipurduar administration launched ‘Apnar Bagane Proshashan’ to conduct meetings with the tea workers; the goal is to respond to workers’ grievances and share awareness of government schemes. In this sense, the aftermath of COVID-19 presents a unique opportunity for the tea gardens of Assam and Bengal – with reverse migration and support from the government this is an excellent opportunity to consolidate and formalize its workforce and strengthen the labour ecosystem of the tea industry in Assam and West Bengal that produces a large faction of the total tea produce.

Reference:

[1] Finance Department, (2020). Budget at a Glance. Government of West Bengal.

[2] Sastry, A. K. (2020). The Hindu. May 05, Retrieved from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Mangalore/reverse-migration-of-workers-hits-plantation-sector-hard-in-karnataka/article31507643.ece

[3] Giri, P. (2020). Hindustan Times., May 14 Retrieved from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/coronavirus-crisis-reverse-migration-gives-hope-to-north-bengal-tea-gardens/story-ibLgfVBQJph2a2UWzVHDPM.html

[4] Bhaduri, T. (2018). The Wire. October 01 Retrieved from https://thewire.in/rights/bengal-tea-gardens-workers-rights

[5] Sharit K. Bhowmik, V. X. (1996). Tea Plantation Labour in India. New Delhi: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

[6] Chakraborty, A. (2020). Assam Tea workers demand wage hike. The Telegraph, June 03.

[7] Tea Board of India (2017) India records highest ever tea production during the financial year 2015-16; exports breach 230 million kgs mark after 35 years. Retrieved from http://www.teaboard.gov.in/pdf/Press_realease_India_records_highest_ever_tea_production_during.pdf

[8] Gplus (2019) Assam Tea Industry Struggles to Stay Afloat; Tea Veterans Ask For Govt Intervention, August 10, Retrieved from https://www.guwahatiplus.com/article-detail/assam-tea-the-challenges-concerns-the-way-forward

Habib Raihan

Anamika Deb