Income inequality to rise in the aftermath of Covid-19

- By Kunal Dasgupta and Srinivasan Murali--

- May 26, 2020

Covid-19, Income Inequality, Labour Market

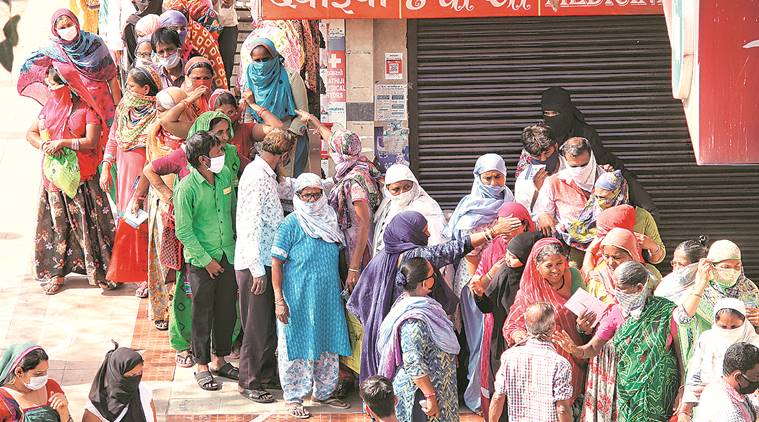

In the last one month or so, India has been haunted by images of migrant workers trying desperately to return to their native villages. The plight of the migrant workers, some of whom travelled hundreds of kilometres on foot, has moved an entire nation. Subsequently, there have been loud calls for governments, both at the centre and the states, to ease their hardship. It is, however, not just migrant workers but large swathes of the population that will be adversely affected in the aftermath of Covid-19. Sans government intervention, we are about to witness a sharp increase in income inequality.

The traditional divide in the labour market has been between high and low skilled workers and a large part of income inequality in any modern society has been driven by differences in the earnings of these two groups of workers. From time to time, new technologies have created major disruptions in the labour market, widening the pre-existing inequality between high and low skilled workers. The entry of computers into the workplace in the 80s was one such technological change. Although unintentional and unanticipated, the technological change triggered by Covid-19 is about to cause another major disruption in the labour market, with an undesirable effect on inequality.

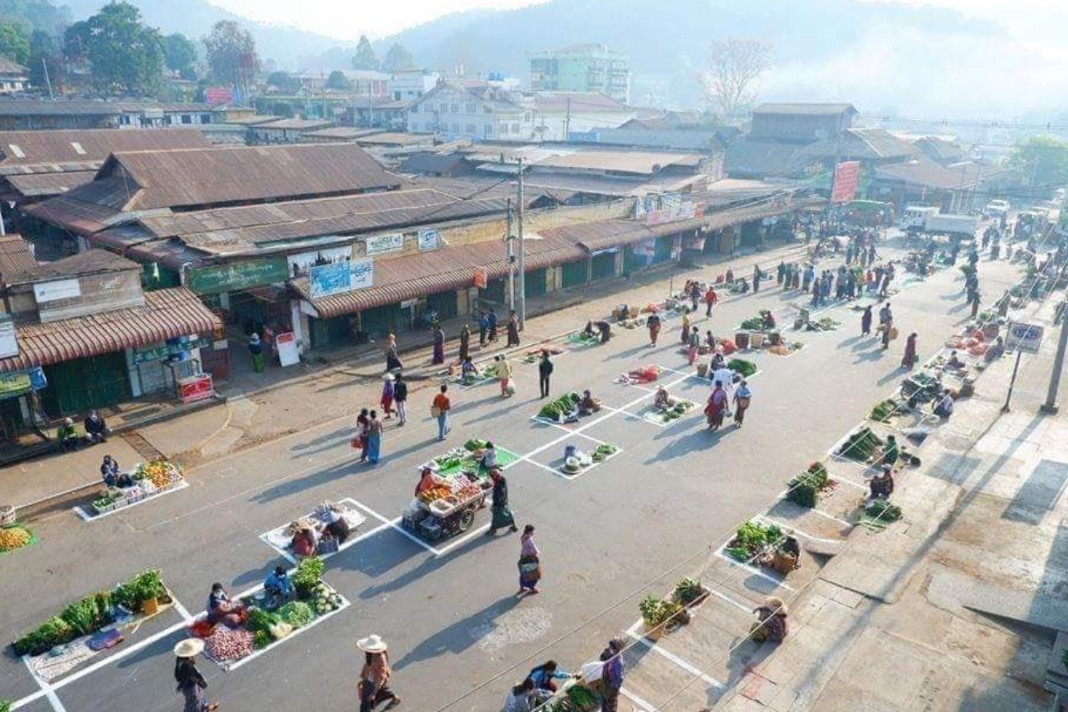

The labour market divide that is relevant in a world where social distancing is the norm is whether the occupation of an individual allows him/her to work remotely/from home. For example, the tasks of an accountant can be carried out remotely without significant loss in the quality of the service; for a machine operator, much less so. And as we argue in Dasgupta and Murali (2020), the ability to work remotely is much higher in occupations typically performed by high skilled individuals. Combining data from various sources, we show that 32 out of 100 high-skilled workers in India can work remotely. For the low skilled workers, the corresponding number is 4. These figures suggest that as lockdowns and social distancing norms cause businesses to reduce the strength of their traditional workforce, it is the low skilled workers who will experience a much bigger decline in their job prospects.

Rising income inequality will follow.

In Dasgupta and Murali (2020), we embed a standard epidemiological model of a pandemic into a macroeconomic framework to examine how Covid-19, and the subsequent measures adopted by governments to check the disease spread, might affect income inequality between high and low-skilled workers in India. Given the uncertainty surrounding the evolution of the pandemic, we examine different lockdown strategies that vary in terms of how restrictive labour mobility is. For example, in one scenario, mobility restrictions are in place for an extended period of time and then removed in one go. In another scenario, the government eases mobility restrictions gradually. We find that depending on the scenario being considered, the increase in income inequality could be anywhere between 3 percent and 21 percent. And this change is expected to happen in just one year. Just to put things in perspective, following the liberalisation of the Indian economy in the early 90s, the same measure of inequality rose by roughly 10 percent over six years!!

Surprisingly, the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown could also increase inequality in health outcomes between the high and low-skilled. This is not because of unequal access to the health care system or a different propensity of getting infected across the two groups, although these are valid concerns. Rather, the inequality is a result of workers responding optimally to the pandemic and the subsequent restrictions. The possibility of getting infected encourages high skilled workers to stay at home. The low skilled workers, however, do not have this luxury. As they step out to earn their livelihood, the probability of contracting the virus rises. Once again, the differing nature of their occupations leads to an increase in inequality between the two groups.

So, what can be done to prevent this rise in income inequality? The answer, of course depends on how the lockdown plays out, which, in turn will determine the corresponding effect on inequality. Our calculations suggest that if inequality rises by 21 percent, direct government transfers to the tune of almost 0.3 percent of GDP, targeted towards low-skill workers would be required. One needs to keep in mind that this transfer would simply prevent inequality from rising; the low skilled (and the high-skilled) would still experience a reduction in their income levels.

We further find that, these transfers on top of averting the increase in income inequality also reduces the inequality in health outcomes between high and low-skill workers. These direct transfers help the low-skill workers to stay back at their homes and not venture out to earn their livelihood. This helps in slowing down the spread of infections among the low-skill workers. In our paper, we show that direct transfers serve both as an economic and health policy and should be used along with various containment policies for acting against the pandemic.

Data Sources:

Kunal Dasgupta

Srinivasan Murali